|

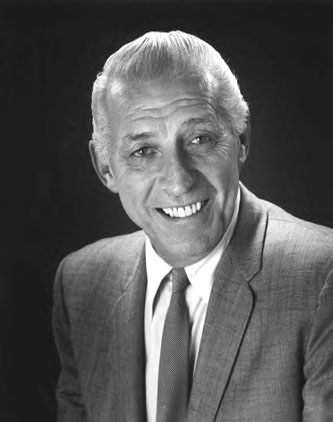

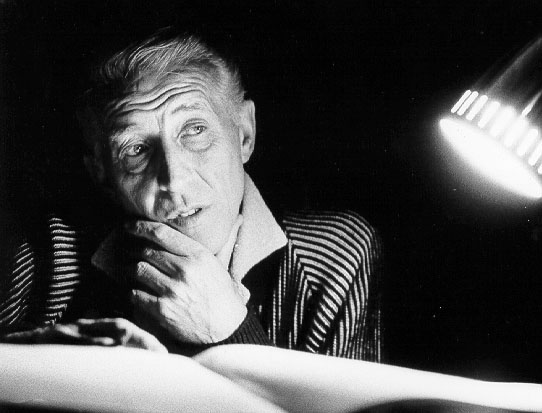

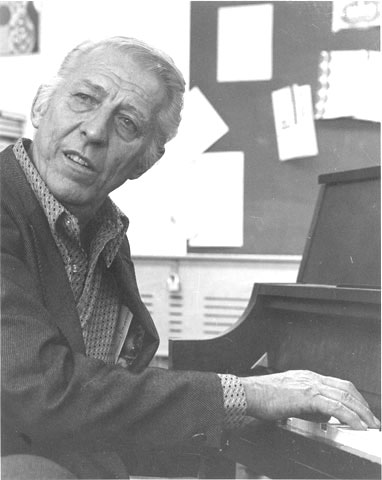

MUSICIAN STAN KENTON

His Experiments Broke Down Jazz Barriers

J. Bonasia

'Investor's Business Daily' February 6, 2001 |

|

Big band leader Kenton was a popular but controversial pioneer who pushed the boundaries of jazz music from the 1940s through the 1970s. In many ways, his bold innovations changed the sound of jazz forever. The pianist incorporated a wide range of styles -- including classical music, opera, Latin beats and ever country western -- into his long career. An energetic performed and creative arranger, he experimented with unusual time signatures, brisk rhythms and wild instrumentation. Some of the most enduring songs by the Kenton Orchestra include: 'Artistry in Rhythm,' 'Eager Beaver,' 'Intermission Riff,' 'Here's That Rainy Day,' 'Street of Dreams,' 'My Funny Valentine,' 'Peanut Vendor,' and 'Malaguena,''Moonlight in Vermont.' Throughout his career, Kenton focused on his goal: Define the future of jazz, not just replay the past. He despised nostalgia and reminiscing so much that he often refused to play requests from his musical backlog, preferring to focus on his newer material. "Never look back," he advised fellow band members, "It's lost energy." Virtually all big bands relied on standard four-beat time signatures, but Kenton wanted something more aggressive. In constant experimentation mode, he arranged songs with odd meters and complex harmonies in a quest for dynamic and moving sound. Most swing music at mid-century was based on a single melody, Kenton was looking for more, however. To punch up his songs, he layered different melodies on top of the lead line so that rhythms and harmonies complemented each other. He also relied on dissonant chord structures to vary the sound. Kenton's inventiveness earned him a devoted following. Yet his iconoclastic approach ruffled the sensibilities of some jazz purists. One critic described Kenton's tireless experimentation as an 'ecclesiastical obsession.' Kenton ignored the critics and kept right on experimenting.

Kenton was fascinated with music early on; his mother was a classical piano teacher and often taught students in their home. She taught Kenton to play when he was 10. He discovered jazz in his early teens and joined his first quartet as a pianist while in high school. During the 1930s, he toured with little-known bands across California, Nevada and Arizona, honing his musical and net-working skills. By 1941, Kenton started his own band, naming it the 'Artistry In Rhythm Orchestra' after his signature song. All his touring paid off; the network of people he met on the road helped the band land its first big booking at the Hollywood Palladium. Kenton combined imaginative saxophone lines with bright trumpets and pumping trombones in his orchestra. He looked for people who enjoyed interpreting music as much as he did. Vocalists June Christy and Anita O'Day joined talented young soloists such as saxophonist Art Pepper, trombonist Kai Winding and drummer Shelly Manne. The band's originality attracted youthful fans who appreciated its brash, loud sound. By 1945, Kenton's unique type of progressive jazz was catching on nationwide, from the Rendezvous Ballroom in Balboa Beach, California to New York City's famed Birdland jazz club. In June 1948, Kenton's orchestra sold out the 15,000 seat Hollywood Bowl and a special midnight concert at New York City's famed Carnegie Hall. For Kenton, such success was only a springboard to new direction: He wanted people to really listen to the music as well as dance. In 1950, he introduced the 'Innovations In Modern Music Orchestra,' an elaborate 43-piece lineup that included a woodwind section, two French horns and 16 strings. The standard big band sound was derived from saxophones, trumpets and trombones. But Kenton's use of reed instruments such as French horns, bassoons and oboes gave him the more mellow sound he sought. The Innovations Orchestra as created to combine the best elements of jazz and modern classical music. While the orchestra marked a creative watershed, the huge expense of touring made it a financial disaster. Kenton lost about $250,000 on the project over two years. Yet he didn't see it as a deficit. "The Innovations Orchestra was a great thing artistically, and to this day I think it was one of the highlights of my career as a band leader," Kenton recalled.

Kenton thought of his rhythmic experiments as an important form of musical expression. And he believed sophisticated arrangements on tunes like 'City of Glass' provided a complexity that was lacking in typical dance orchestras of the time. "There are many more emotions that can be portrayed and felt in addition to just swinging," he said. "Swinging is a happy thing and most swing is happy. But other emotions must be expressed, too." When Kenton acted, it was boldly. After a tour in Ireland in 1953, Kenton scaled the Orchestra back to a 19-piece group that had an unexpectedly swinging sound. Then he collaborated with cowboy singer Tex Ritter on a collection of country-western tunes. Kenton said he hoped the country project would "break down some of the bigotry in music." The record was a failure, disappointing jazz fans and critics. He didn't give up. Kenton next put out his Kenton/Wagner record, in which a 25-piece group played arrangements of themes from Richard Wagner's opera, including 'Ride of the Valkyries.' Jazz aficionados also ridiculed this foray into opera. Then, as electric rock started to drown out big bands in the 1960s, Kenton took another bold step. He introduced his 23-piece 'New Era In Modern Music Orchestra, which featured four mellophoniums. In 1961 Kenton ingeniously used the mellophoniums, which resemble front-facing French horns, to bridge the gap between the trumpet and trombone registers. Unfortunately, the mellophoniums were difficult to keep tuned and the band broke up in 1963.

Dan Salmasian, an adjunct music professor at Florida Atlantic University and Barry University, was in his early 20s when he toured on sax with Kenton from 1974 to 1975. Salmasian called Kenton "a free spirit who had a marvelously different way of looking at things.' Trumpet player and Kenton collaborator Maynard Ferguson noted the importance of Kenton's contributions, especially his willingness to defy established conventions. "Stan was always experimenting. He never stood still," Ferguson said. "Maybe he didn't always go in the direction people wanted, but at least he set out to do what he wanted to do. He had the integrity of his own musical beliefs." Kenton wanted others to love jazz music as much as he did. To that end, he gave performances, clinics and seminars at schools and colleges nationwide throughout his career. During the 1960s and 1970s he developed 'Jazz Orchestra In Residence' clinics at many universities. His effort in the schools was based on his belief that the future of progressive jazz depended on the education system, not the commercial sector. Kenton died in 1979 after a bout of health problems.

|

|

|

Stan

Kenton followed the beat of a different drummer --

literally.

Stan

Kenton followed the beat of a different drummer --

literally. Stanley Newcomb Kenton was born in Wichita, Kansas in

1911 or 1912 (the date is disputed) and moved to Los Angeles with his

family in 1917.

Stanley Newcomb Kenton was born in Wichita, Kansas in

1911 or 1912 (the date is disputed) and moved to Los Angeles with his

family in 1917. Another

Kenton innovation was the use of Latin rhythms and

themes, including the breakthrough 'Cuban Fire' album written by Johnny

Richards. That record featured various Latin-style percussion

instruments such as bongos, congas, timbales, claves and maracas. The

record's punchy rhythms propelled a honking brass section.

Another

Kenton innovation was the use of Latin rhythms and

themes, including the breakthrough 'Cuban Fire' album written by Johnny

Richards. That record featured various Latin-style percussion

instruments such as bongos, congas, timbales, claves and maracas. The

record's punchy rhythms propelled a honking brass section. Determined to give jazz music a shot in the arm, Kenton

came roaring back two years later with his 28-piece Neophonic

Orchestra. The group played neo-classical songs from some of the

year's finest composers, including Nelson Riddle, Mel Torme, George

Shearing and Shorty Rogers.

Determined to give jazz music a shot in the arm, Kenton

came roaring back two years later with his 28-piece Neophonic

Orchestra. The group played neo-classical songs from some of the

year's finest composers, including Nelson Riddle, Mel Torme, George

Shearing and Shorty Rogers.