|

STAN KENTON SPEAKS OUT Down Beat Magazine Interview, December 20, 1973 Conducted

by Peter Newman |

|

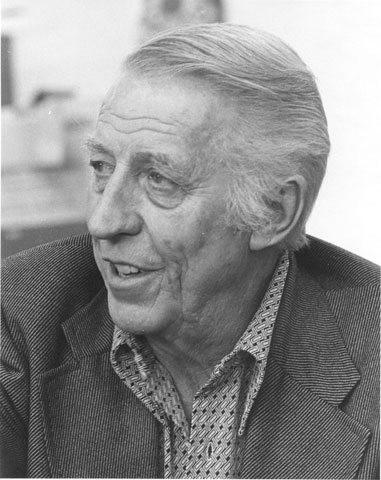

The

Kenton band, which started as a hybrid offshoot from the rhythm machine

put together by Jimmie Lunceford in the late 1930s, has never stopped

groping for new sounds. Late in his middle age, Stan Kenton continues

to evolve his concepts of jazz, and it remains as difficult as ever to

be neutral about the man and his music. Critics and jazz buffs are

more sharply divided about the true worth of his music than about any

other jazz giant. But Kenton goes on, playing his craft with

dignity and humor, a man and a musician firmly in command of his worth. After

a recent concert in Ottawa, Canada, I recorded the following interview.  Newman: While youve never had any problem communicating with your listeners, it seems to me that you have often been misunderstood or misrepresented by the critics.

Newman: Maybe the problem is that your music is too subtle, too complicated. It isnt jazz that just swings. Kenton: They seldom complain that its too complicated. They say the music is contrived, pompous, melodramatic and things like that. But, you know, its pretty hard to contrive anything, especially music. Take an author, for instance, he might think. Well now, maybe this is a little complicated. Am I going to lose a few readers if I publish this? And he might retrace his steps and say, I believe I should edit this in or out or something. And I do that with my music, but you dont ever move too far from what you basically believe in, from what you are. Newman: With such a large band (19 pieces), and such intricate arrangements, how do you maintain the spirit of improvisation in your music? Kenton: I think there is a great fear of a band thats playing the same music all the time, starting to play by rote, and I cant have that, because I like the thing to be almost like a new experience every time the band plays. So I always keep after the soloists and tell them to take chances, not to get involved with clichés and all that kind of stuff. Take wild chances, I tell the rhythm players, because if you dont take chances you arent going to come up with any fresh excitement. When Im conducting the band, they never know what the hell Im going to do because if they knew where my hand is going to come down, they just look off into the trees somewhere. But they never know whats going to happen. It keeps everybody on their toes so that the band has a spontaneous sound thats a form of improvisation too. Newman: Youve been on the road for more than 30 years now and youre 61 years old. It must be a really tough grind. How do you keep going? Kenton: I dont think its so tough, if you have the privilege to do what you want to do and to enjoy the freedom that I enjoy. All the little inconveniences that I might suffer on the road are more than compensated for by the freedom I have. If I had taken a job conducting a television show somewhere, or doing background music, Id be at the mercy of some idiot producer and I wouldnt have any freedom. As it is, I am free. Newman: That freedom is reflected in your music. It seems to me that your road bands have always been better than your studio orchestras. Kenton: Yes, theres nothing like an organized band. Los Angeles and New York are full of musicians who used to play with me, but they could never sign up with this band. Not even if you got the finest of them together. Its a whole different approach to playing. These guys are together all the time, and when they leave the band and try to start fitting into freelance jobs, they have to water down what they believe in. I doubt if some of the musicians who have left the band could ever even play this kind of music. It would be too hard for them. Funny thing about the band, too, is that most of the guys whove left it in the past still refer to it as their band. Were all very good friends. They come around and we see each other all the time and theres a great feeling of belonging to each other. Newman: What is the Kenton sound? Is it mostly a matter of broad voicing? Kenton: Its a lot more than voicing, but I cant really define it. Its one of the mysteries of the communication that exists between the guys and myself. And its something thats almost on a subconscious level. Im not really conscious of it, and I dont think they are either. But you could put me in front of a strange bunch of guys and sure as hell, after a few weeks, theyd sound like the Kenton band. Newman: Yet there has been a very constant sound to all of your orchestras. Perhaps you look for it when youre picking your musicians. Lead trombone, for example: Kai Winding, Milt Bernhart, Bob Burgess and Dick Shearer (whos with the band now), sound remarkably similar. Kenton: Yes, there is that. Certain guys are attracted to the band. A Tommy Dorsey-type trombone player wouldnt make it. Newman: How did you get into the time signature experiments that Hank Levy is writing for you now?

Newman: Is it really possible to play jazz in 7/4 time, or 20/16 time? Kenton: When you get right down to it, its divided into accents. If a thing is in 7/4 time, its never divided into more than three units. In other words, if it is in 7/4 time it can be divided one-two; two-two-three; three-two; or you could have one-two; two-two; three-two-three, etc. Those are the basic accents. When you get up into advanced time signatures youre really familiarizing yourself with a series of accents. But you count, at first, in order to get the feel of the thing; once its going, then you know what kind of accents its in. Newman: I heard that Levy was starting to use violins in his own band. Kenton: Yes. You see, we all feel morally obligated to the kids, and none of them want to play violin. They just want to play trumpets and trombones and drums and saxophones. I dont know what the hell the symphony orchestras are going to do for violin players one of these days. That was my idea with the Innovations Orchestra, to see if we couldnt break the strings loose into a modern way of playing, and get over the old European gypsy thing. Things we did with strings in the Innovations Orchestra were very good, but we couldnt afford to keep going with it. I think that if kids knew that string players could sound a different way than they do, they might be attracted to the instruments. Newman: Would you ever go back to the mellophonium? Kenton: Yeah, Id like to, one day. It was strictly a money thing that caused us to have to do away with them. Oh boy, I loved those horns. Newman: How do you recruit new musicians? How did you sign Mary Fettig? Kenton: I get musicians mostly through the recommendations of guys in the band. Now Ive known Mary ever since she was 13 years old. She used to come down to the Redlands jazz clinics. Two years go I was sitting on the lawn under a tree, trying to cool off, and she came along and sat down next to me and introduced herself. I asked, This is the year youre going to graduate from high school? And she said shed just graduated. So I said, What are you going to do? Are you going to go to college? And she said, Yeah. I said, What do you think youre eventually going to do with your music? Are you going to teach? She said, No. And I said, Well are you going to give it up and get married? And she said, No. So I asked, What are you going to do? and she said, Im going to play saxophone in your band. That was two years ago. (Shes 20 now.) Everywhere we went in the States, the girls were playing everyplace, and they always came up to me and said, Dont you want my girls in the band? So in the back of my head I thought about Mary. When the chair opened up I said to John Park, Youre the boss of the section, you pick the guys youre going to play with, would you consider having a girl, if she could really play? He said, Sure. So I contacted Mary. And I said, Lets be honest about this thing, John, if she doesnt make it you let me know and get her out of there. So after we played a set, a couple of weeks after she came with us, I went over to where John was and I said, John, what do you think? He told me, She scares the hell out of me. She reads better than any of us. Newman: I dont know the genesis of it, but theres always been a story floating around about black musicians in the Kenton band.

Newman: I notice that a lot of kids come to your concerts. How do they learn about your music? Kenton: Four or five years ago, when mass merchandising of records prompted me to fight back by starting the Creative World label, agents and bookers kept thinking of the band as being old-fashioned. They were constantly trying to book us into American Legion Halls and Elks Clubs. So I said, Theres got to be another way to reach those kids. Now, we cant reach them through the radio because radio wont play the stuff, but weve got to get these kids to hear our music, because I firmly believed that once the kids heard it, they would buy it. So with the Redlands album, we first started pushing this concept of jazz orchestra in residence to get into the schools. And boy, I sure was right. They are organizing their own live bands and jazz ensembles now and the thing is going crazy. I dont know whats going to happen. Weve done it for as many as 2,000 young musicians and 50 band directors at one time. Newman: Where will all this lead? What kind of outlet for their talents will all these young musicians have? Kenton: A lot of us used to get the guilt's around the clinics years back, wed ask ourselves, What are we doing teaching these kids this kind of music when theres not going to be any place for them to work? Finally, I began to see another side. They dont have to play music for a living. But its given them something and theyre going to go out and be creative human beings. An education in jazz music is a very important part of developing a mature, creative mind. I dont think theres any subject other than music that can contribute to so many different facts of the development of the mind. Its a universal language. And specifically jazz, because honest to God, every guy Ive met who is a successful, achieving human being and is tuned in and aware, either used to play jazz as a kid or else was addicted to it. Its the wildest thing. Id like to see jazz music become compulsory in schools some day. Newman: Whats your reading of current trends in the music industry? Kenton: Oh, I have some wild theories. Every time I get to talking about them, people think Im nuts, but I think that one of these days record collections are going to become antiquated. I think people are going to look for a now experience in music and seek out live performances, more than anything theyve ever experienced in the past. Its not going to be a static thing anymore. The idea of people wanting to hear music played live and in person is very healthy thing. Newman: What about the direction of jazz itself? Kenton: Anytime something comes along, like new time signatures, or this talk about different scales and getting into quartertones and 35-tone scales and all that, I feel that we still havent scratched the surface as far as the 12-tone scale goes. I think that what we need most is composers, guys who can write great themes. The trouble is, many writers get restless and they start to go in for freak things, using gimmicks and a whole lot of crap like this electronic music today. Its a cover-up for talent. It distorts the communication between a player and a listener. It takes on a synthetic sound. Newman: How do you read the future for big bands?

Kenton: About five or six years ago we were having all kinds of trouble getting booked, and one time I went out to lunch with the head guy of an agency in Chicago, and he said, Well, Stan, lets face it. What do you play for the kids? I said, Im not playing anything for the kids. If I start playing for the kids what the hell are they going to shoot for? He said, Well, after all, its a kids market today. I said, Oh, bullshit, its not a kids market. And thank Christ, in the last four or five years Ive proved my point, and when the kids hear the band blowing, boy, they want some of that. But the parents, they havent done much good either. They keep nagging at their kids and telling them, You should listen to music like I used to listen to when I was a kid. The kids finally say, O.K., play me some of it, and they get a little Tommy Dorsey record out and nothing happens and the kids say, Phew! But when they hear some of the modern bands play the strength and the energy that comes out of those horns boy, then they say, Thats for me! Newman: How do you treat the whole concept of nostalgia? People must be pretty disappointed if they turn out to hear your band and expect to hear 'Eager Beaver'. Kenton: I think that people who are constantly dwelling on the past have a form of sickness. Maybe theres a psychological reason for it, maybe theyre reluctant to accept the present and are afraid of the future. Maybe they feel that if they made it 20 years ago, they can go back and make it again. Theres got to be something like that which motivates nostalgia. And of course, theres no more commercial commodity today than nostalgia. I dont care if its Europe, or here, or anywhere. It makes you sick. When somebody comes running to me and says lets talk about the good old days I say, Christ, Ive got more appointments than I can muster up, and phone calls Ive got to make, and I get out of their clutches.

Kenton: Yeah, but have you ever gone to hear Buddy de Franco and the Glenn Miller band? God, I heard him in Chicago one night at Mr. Kellys. We had a night off and they played 'Serenade in Blue' and 'Pennsylvania 6-5000' and 'I've Got a Gal in Kalamazoo' and all that awful stuff. It was all right at the time but Goddamn, this is 1973. Newman: Are you saying that there will be no Kenton ghost band? Kenton: Well, I dont think there will be. Ive told everybody connected with me, When I die, the thing dies. I dont want anybody running around trying to play 'Intermission Riff'. Newman: Why do so few people in our society recognize jazz as an art form? Kenton: Well,

the

problem is, you have to be gifted with a certain amount of perception

to communicate with jazz. Many people dont have that kind of

perception. After all, jazz is an abstract form of communication

and you have to have perception to communicate with

abstracts. Your mind has got to work for you, your fantasies have

to come alive. People who dont have any fantasies cant

communicate with anything abstract. So thats why jazz can never

be a mass music, the masses arent gifted with perception. Its

only a small minority group. Its painful to think that thats the

way it is, but I guess thats the way its always been, and the way it

always will be. |

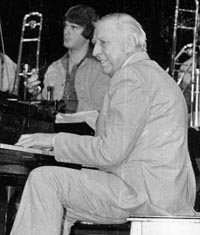

Big band jazz

these days is in a period of minor renaissance. Among its most

active and controversial exponents is Stanley Newcomb

Kenton, the pianist-leader-arranger who has influenced and haunted

contemporary American music since his first band opened the 1941 season

at the Rendezvous Ballroom in Balboa, California. His current

reincarnation marks a curious turn in the long musical life of a man

who has seldom been in tune with the rhythms of his time. After

thirty years of fronting just about every format into which the jazz

orchestra can be expanded and playing nearly all the musical tempos

known to man, Kenton is back with, of all things a road band airy

and free that is gaining recognition and converts everywhere it

plays.

Big band jazz

these days is in a period of minor renaissance. Among its most

active and controversial exponents is Stanley Newcomb

Kenton, the pianist-leader-arranger who has influenced and haunted

contemporary American music since his first band opened the 1941 season

at the Rendezvous Ballroom in Balboa, California. His current

reincarnation marks a curious turn in the long musical life of a man

who has seldom been in tune with the rhythms of his time. After

thirty years of fronting just about every format into which the jazz

orchestra can be expanded and playing nearly all the musical tempos

known to man, Kenton is back with, of all things a road band airy

and free that is gaining recognition and converts everywhere it

plays. Kenton

Kenton Kenton

Kenton Kenton

Kenton

Newman

Newman