|

Stan was everything

and nothing like his audiences imagined him to be. He was the antithesis

of his stage persona: brilliant, but tortured;

generous to a fault yet tight-fisted when it involved salaries and

expenses. He could also be unfathomably complex at times but just as

quickly transform himself into someone rather naive about the world he

lived and worked in. I, for one, was continually amazed at how innocent he

was when it came to dealing with less than trustworthy promoters and deal

makers.

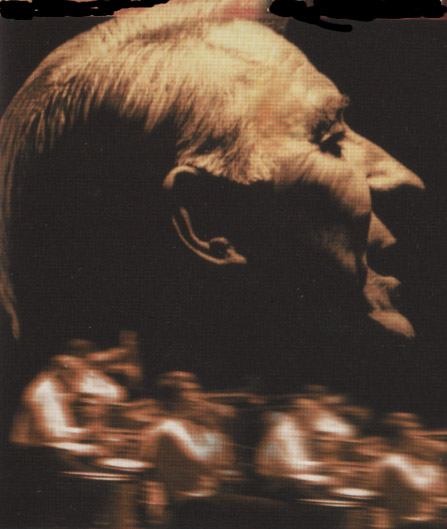

Standing before an audience Stan had a magisterial presence; a

patriarchal sense of power and authority. There was no doubt he had

more than his share of charisma, but how much

of it was real, and how much of it was a figment of someone’s

unrealistic imagination we’ll never quite know.

People he had only a passing acquaintance with (his phenomenal gift for

remembering names

more often than not was a burden, rather than a helpmate) led them to

believe he was

genuinely interested in catching-up with everything that had been

happening in their lives.

Nothing

was further from the

truth. Small talk bored him. He was not, as many close to him

were aware, an

articulate conversationalist since he hardly ever opened a newspaper or

read a

book. He was interested in only three things; his music, the

Orchestra

and gossip. He

thrived so much on hearing juicy tidbits about people in and out of

show

business we nicknamed the ‘Rona Barrett of the bus'. Nothing

was further from the

truth. Small talk bored him. He was not, as many close to him

were aware, an

articulate conversationalist since he hardly ever opened a newspaper or

read a

book. He was interested in only three things; his music, the

Orchestra

and gossip. He

thrived so much on hearing juicy tidbits about people in and out of

show

business we nicknamed the ‘Rona Barrett of the bus'.

No one had to tell Stan how

the Orchestra sounded. He,

more than anyone, knew what it took to keep the it sounding like a

well-oiled,

precision disciplined machine capable of creating a breathtaking range

of

dazzling

emotions, which was one of the reasons he kept the arrangers busy

expanding the library.

It

was not unusual for us to

leave Los Angeles with a library of 200 scores and return with more

than 350.

Many

of which

were played only once, then relegated to the bottom of the book never

to be

played again.

An exception was Dee Barton’s brooding, brilliant arrangement of ‘Here’s That Rainy Day’ which was used

as the set piece that opened a concert or dance engagement and

was often played twice in a night depending upon Stan’s mood.

On the

road, Stan’s mercurial personality was a study in contrasts. For weeks,

sometimes months, he would be out-going, tolerant of minor missteps

both on the

bus and

bandstand, generous to a fault and take great delight in his role as a

surrogate father to 22 wandering minstrels. He also possessed seemingly

inexhaustible reservoirs of energy belying the fact he had spent over

25 years on the Road.

Then,

like lightning, his temperament would turn dark, brooding and

malevolent. For

no apparent reason he would became mean, sarcastic, petty, unforgiving

and

unreasonable. When this happened everyone gave him a wide berth, both

on the

bus and on the date, because no one wanted to run the risk of having

him ream

them out over some petty transgression. Or, worse yet, decide to

fire them

a thousand miles from home.

I think

he was acutely aware the Orchestra's temperament was dependent upon his

mood.

That when he was happy everyone was happy. Yet there were times he

could have

cared less if the guys were under real or imagined pressures or going

through a

tumultuous period

in their lives. Being away from home and their girl friends or wives

for months at a time took its toll and could make for some frazzled

personalities. Stan felt the pressure, too, and for days he walked

through the dates like a zombie

unable

to disentangle himself from the many problems that had begun

manifesting at home and on the Road.

Eventually,

the problems at home and the problems on the Road would become so

burdensome

Stan merely went through the motions as our leaderless Orchestra moved

listlessly from

job to

job. The strenuous emotional challenge involved in keeping Stan's home

life

separate from his professional life was compounded by his excessive

drinking.

There

were problems

with his pending divorce from Ann Richards . Problems with the

kids rebelling against school and being left in the care of a less than

competent housekeeper. Problems meeting the payroll. Problems with

Capitol not

promoting his albums . Problems with his career veering off center

because of

inept personal management. Problems with a musician or two who had begun

slacking off and missing cues. Problems with alcohol which were

becoming

ever more

serious as he grew older. Problems with his health. Problems. Problems.

Problems. They never seemed to go away.

For the

most part he was able to keep his professional life separate from his

personal

life. There was the Stanley Kenton (none of his friends or the Band

ever called

him Stan) who lived with his children

in Los Angeles. Then there was the Stan Kenton, who led an orchestra

and

lived 300

days on the Road.

Two vastly dissimilar alter egos which merged together and

often clashed for no apparent reason. The Stanley Kenton who lived at home

was a caring, loving Father devoted to his children, who couldnt wait to

get back out on the Road. Two vastly dissimilar alter egos which merged together and

often clashed for no apparent reason. The Stanley Kenton who lived at home

was a caring, loving Father devoted to his children, who couldnt wait to

get back out on the Road.

The Stan Kenton who spent 10 or more months on the Road and

who was a surrogate father to 22-extraordinarily talented musicians, was

constantly racked with guilt because he wasnt spending more time with his

two young children, Lance and Dana.

Although

he never drank before or on the job, he would begin consuming copious

amounts of alcohol minutes after the final notes of the Band’s theme

drifted

off into the late night and within 40-minutes be totally inebriated.

Yet, In a fit of perversity he often lashed out at the men,

castigating them for drinking too much and working the job with a

roaring hangover.

The men found it bewildering, given his own problems with alcohol, that

he

thought nothing of singling one of them out for a severe

tongue-lashing,

followed by calling him a 'juice head',

a label which usually signaled the guy’s demise on the Band.

During

these times only a true Kenton aficionado might sense a lack

of esprit

de corps and realize something was missing between leader and

Orchestra. To the

trained ear the solo work sounded dull and listless and lacked the

intoxication

one underwent when touched by a brilliant player’s virtuoso

performance. The

ensemble work not only sounded flat and disjointed and had lost its

buoyancy, it

also had lost its ability to move out and across an audience like

sheets of crackling thunder.

Even the Orchestra’s signature, stratospheric trumpet work had lost its

snap

and sounded fractionated. These were not good nights and it amused us

to hear

some sycophant fan gushing to Stan

between sets:

“God,

Stan, the Band sounds fantastic tonight.”

Oddly

enough, most fans had not come to hear the music. Most couldn’t tell a

Kenton

arrangement from one written by Holman or Richards or Roland. Although

Stan was

fond of describing his music as an “intellectual stimulus for a very

select

audience anxious to expand their musical awareness,” most Kenton fans

were

musical illiterates, incapable of being able to distinguish a quarter

note from a

sixteenth or understanding the difference between minor and major keys.

They

were there to bask in the aura of the Kenton mystique. To reach out and

touch

the mantle of someone, who, through their unfailing support, had been

transformed into a mythical legend. It was not unusual to see someone

tightly

clutching a album cover or ragged piece of paper for him to sign,

approach him

and hyperventilate when he asked their name so he could personalize the

autograph for them. one written by Holman or Richards or Roland. Although

Stan was

fond of describing his music as an “intellectual stimulus for a very

select

audience anxious to expand their musical awareness,” most Kenton fans

were

musical illiterates, incapable of being able to distinguish a quarter

note from a

sixteenth or understanding the difference between minor and major keys.

They

were there to bask in the aura of the Kenton mystique. To reach out and

touch

the mantle of someone, who, through their unfailing support, had been

transformed into a mythical legend. It was not unusual to see someone

tightly

clutching a album cover or ragged piece of paper for him to sign,

approach him

and hyperventilate when he asked their name so he could personalize the

autograph for them.

Eventually

the day would come when Stan began gradually slipping the bonds of

lethargy and

came to grips with his demons before they completely paralyzed him.

Once

this happened he would be the first one on the bus effusively greeting

everyone

by name as they climbed on board,

reaching out and patting them on shoulder as they struggled with their

gear

down the aisle. Even those who had awakened in a foul mood found they

couldn’t

resist his radiant smile and infectious laugh as he made small talk

with those in the front

compartment.

Moments

after the bus was locked down and Eric began moving it into traffic

Stan would

take his command position in the side door well letting everyone know

that once

again he

was off and running, anxious to pull the Orchestra back together again.

We

continually marveled at how his temperament could change from a

borderline android, who had been fumbling his way from one job to the

next, to the

highly-energized, bigger-than-life Road warrior we all loved and

admired. Today

he might well have been diagnosed as a clinical manic depressive who

forced

himself to face the world, relying only on some inner strength to carry

him

forward

until the black cloud of depression that had mysteriously and without

warning enveloped him passed.

Every

group, especially one as large and complex as the Kenton Orchestra,

requires a

captain with

a steady hand to keep it sailing safely through uncharted waters. In

our

case the

long, unpredictable Road. And no one was more aware of this

than Stan,

who knew when and how to bring the Band back from the edge of darkness.

Usually

his ill-humor never lasted more than a day or two. Three at most. One

incident,

however, which lasted not quite a week took all of us to the breaking

point with

his abjection. Usually

his ill-humor never lasted more than a day or two. Three at most. One

incident,

however, which lasted not quite a week took all of us to the breaking

point with

his abjection.

It

happened one night, about an hour out of Memphis,

where we had performed to less than 500 people at a ballroom that had

seen

better days. Tennessee

was

predominantly a country-western culture and none of us ever understood

why our

booking agency accepted play dates anywhere other than Vanderbilt

University and the University

of Tennessee, both of whom thoroughly

enjoyed having the Band perform at

their proms.

Adding to the disappointment of a less than productive date was the

knowledge the county the ballroom was located in was dry. If you wanted a

drink you had to bring your own bottle. The only thing served at the bar

were setups and soft drinks. Once the word was passed that there would be

no booze available the guys began exhibiting all the classic signs of

withdrawal. Dry mouth. Stomach cramps. A slight case of the shakes.

Irritability. They had been counting on being able to get a drink at the

bar during the breaks since we hadnt made a liquor stop in two days.

There wasnt so much as a can of warm beer left on the bus.

The Road

Manager, who was charged with maintaining a weekly schedule of

all the

locations we would be playing at and any problems we might encounter

buying

liquor enroute had blown it. Even Stan, who enjoyed relaxing with a

bottle

of J&B Scotch every night, was put out and asked Eric, our bus

driver, if

he would mind returning to Memphis and picking-up whatever anyone

wanted.

Unfortunately for the one’s who were showing signs of early withdrawal Eric wouldn’t be able to leave until the

instruments were unloaded and the bandstand set up; at

least

another hour. As one might expect the guys began wandering around,

complaining they

wouldn’t be at their best unless they had “a taste to loosen their

tonsils."

They made it quite clear they were not pleased with the Road Manager

and would

have no hesitation about leaving him behind when the dance ended around

1 o’clock.

Eric

wasn’t too pleased either with having to drive back to Memphis, find a

liquor

store that was open and locate a place to park a 40-foot bus while he

went in

and picked-up 40 to 45 bottles of liquor. Even a skilled driver like

Eric found

it nerve-wracking to try and maneuver the bus down narrow city streets,

searching for wide enough intersections

in order to negotiate right hand turns without climbing the curb. Everyone

had put in a double order since the next day was Sunday and nothing

within

400 miles would be open until Monday morning. Eric, however, was adept

at

handling assignments of this nature and after 20 years of driving Kenton Orchestras all over the United

States, Canada

and Mexico,

little, if anything, fazed him. Unfortunately the only place to park

was on the

street directly in front of the store. Eric

wasn’t too pleased either with having to drive back to Memphis, find a

liquor

store that was open and locate a place to park a 40-foot bus while he

went in

and picked-up 40 to 45 bottles of liquor. Even a skilled driver like

Eric found

it nerve-wracking to try and maneuver the bus down narrow city streets,

searching for wide enough intersections

in order to negotiate right hand turns without climbing the curb. Everyone

had put in a double order since the next day was Sunday and nothing

within

400 miles would be open until Monday morning. Eric, however, was adept

at

handling assignments of this nature and after 20 years of driving Kenton Orchestras all over the United

States, Canada

and Mexico,

little, if anything, fazed him. Unfortunately the only place to park

was on the

street directly in front of the store.

He hadn’t been gone

5-minutes

when a

squad car, lights flashing, pulled-up and two officers leaped out.

While one of

them stood alongside the bus and began writing a summons the other one,

who was

so obese he hardly fit into his uniform strode majestically into the

store and

asked Eric if that was his bus parked outside and wasn’t he aware it

was

against city regulations to park it on the street? Eric politely

explained to

him he hadn’t seen any signs indicating there was no parking.

“There

aren’t any for cars,” the beefy cop said, taking his campaign-style hat

off and

wiping the perspiration off the inside band with a red checkered

handkerchief.

“The ordinance applies only to buses. Out of town buses!”

Eric,

who had been around the block a few times, knew it was a setup. That

the cops

had seen the California

license

plates and were going to stick it to him.\

“That a

tour bus?” the fat cop asked looking out the window at his fellow

officer.

“No,

it’s a private charter,” Eric quietly answered him.

“Tourists?”

“No, an

orchestra.”

“Orchestra?

Whose?

“Stan

Kenton.”

Never head of him, the c op said taking out a fat plug of tobacco. op said taking out a fat plug of tobacco.

“What if

I move the bus right now? Would I still get a ticket?”

Fraid so. We dont tolerate much people breaking our

laws. Let people do

what they want and all a sudden you got anarchy from one

end of town to the next, can't have that. No siree, bub! the cop said

with a benign smile.

By now

the cop outside had finishing writing out the ticket and walked into

the store

and handed it to with a big smile to Eric.

“You’ll

have to come with us and settle it now,” said the cop ominously as

though Eric

was a wanted felon.

“Can you

tell me how much it will be?” Eric asked, sensing it would be stiff.

“$75.00,

plus $10.00 court costs. Cash only. No checks. We don’t accept

out-of-state

checks!”

Eric

knew he had $225.00, most of which was everyone’s liquor money. After

paying

the fine he’d only have enough to pick-up half the order. Unfortunately

he had

no alternative, knowing full well the cops would impound the bus if he

couldn’t

pay the fine. Thinking quickly he decided to buy as much vodka his

depleted

funds would allow and forego getting any bourbon or Scotch. That

decision

permitted him to add eight more bottles of vodka, bringing the

complement up to

28 fifths. After paying the manager and loading the cases underneath

the bus so

they wouldn’t have an excuse to stop him on the outskirts of town for

having

liquor inside a motor vehicle he rode over to the station house with

the two

officers and paid the ticket.

Before

leaving he politely asked the cops for a ride back to the bus.

“Sorry,”

the beefy one said. “We can’t be chauffeuring people around this time

of night.

We’ve got to make rounds,” he said, swinging his rutabaga-shaped body

into the

squad car as they sped off into the night laughing.

Eric

took his time walking the 10 blocks back to where the bus was parked

since he

was in no great rush to explain to Stan and the guys that half the

money they

had entrusted to him had gone to pay a parking fine. He knew they

wouldn’t give

a damn about the money. It was the thought of having to stretch the

liquor out

for two days before another run could be made that was going to

cause

all sorts of problems. Maybe, once they crossed over into the mountains

tomorrow at noon they could

pick-up

some moonshine. A ghastly, but workable idea, which would appeal to

only the most

die-hard drinkers.

As he

pulled back into the ballroom parking lot he could see several guys standing

around the side door acting as lookouts so they could alert the rest of

the

Band he had returned. They were still on break so a number of

them rushed over and

waited expectantly for Eric to open-up the swing-away luggage doors.

standing

around the side door acting as lookouts so they could alert the rest of

the

Band he had returned. They were still on break so a number of

them rushed over and

waited expectantly for Eric to open-up the swing-away luggage doors.

After

explaining to them what happened and how he had to flush the initial

liquor

order out with extra vodka he went to find Stan, who was arguing with

the

promoter who wanted to cut the Band’s performance fee since only 500

people had

come out to the date. The ballroom owner claimed he had expected at

least

2000 people

to show up to hear the Band, which was an out-and-out lie since there

probably

weren’t more than 1200 people within a 50-mile radius of the

ballroom.

After

listening

to the owner moan, groan, belly-ache and wring his hands about how much

this

date had cost him in added security, parking attendants and advertising

because

“an attraction as famous as the Stan Kenton Orchestra was appearing at

his

ballroom,” none of which was true, Stan agreed to accept $500.00 less

than the

contract stipulated.

Thinking

the guy would be delighted he had managed to filch the Band out of

$500.00, Stan

got up

to see what Eric wanted. Before he had taken three steps the guy yelled

after

him, “Make it seven-fifty and we got a deal.”

Make it five hundred and well play out the night, Stan

told him, rigid with rage that we had been booked into a date from hell.,

otherwise were leaving.

“You’ll

take the seven fifty and

finish

playing or I’ll sue you for breach of contract,” the owner yelled back.

“Up

yours!” an infuriated Kenton told him. “We’ll finish, but you’ll hear

from

Associated Booking’s attorneys.”

He then

walked over to Eric and asked him what was up. Eric explained what had

happened with the police, which

made him

even more tearass.

The

Band

had the last word, however. The

Band

had the last word, however.

They

played the remaining hour and a half,

improvising arrangements done in the style of Lawrence Welk, Blue Barron, Sammy

Kaye and Freddy Martin. It didnt take long before the ballroom began

emptying out as one irate couple after another told the owner they had

come to listen to the progressive sounds of Stan Kenton not swing & sway

music. After demanding their money back they made it clear they would

never return.

There

was nothing the owner could do. Stan had honored the contract to the

full

letter of the law so he had to be paid, although it meant he was

forced to

accept seven hundred and fifty dollars less than what had been agreed

upon. Such was life on the 'Big Bad Band from Hollywood, California.'

A

week later Associated Booking Corporation went to court and secured a

judgment against the owner in the amount of $2500.00

for violating the contract.

Hearing that good news the Band continued on its merry way to the East

Coast, where they were booked into 'Basin Street East' for three

glorious weeks with Oscar Peterson and Chris Connor.

It was, for

the 1961 Stan Kenton Orchestra, the date of dates!

|